Charles Saumarez Smith interview

The former Director of the National Gallery talks about the future of art museums and what makes Louvre Abu Dhabi so impressive

There are few people more qualified to examine the evolution of the art museum than Sir Charles Saumarez Smith. Over nearly 25 years he was at the helm of some of the UK’s biggest art institutions: he was appointed Director of the National Portrait Gallery in 1994, Director of the National Gallery in 2002 and finally Secretary and Chief Executive of the Royal Academy (RA) in 2007. He knows what makes art museums tick.

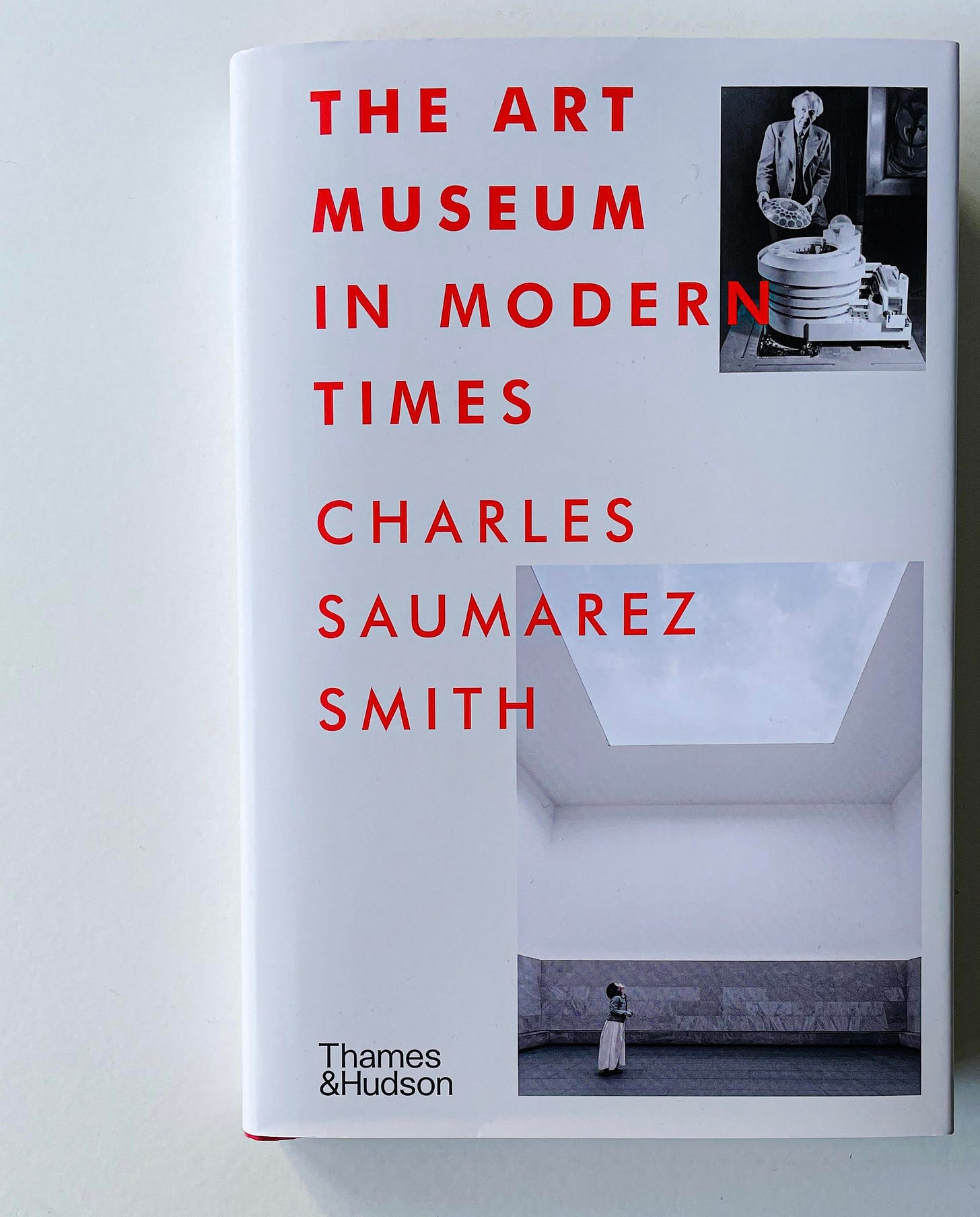

It’s this experience that makes his new book, the Art Museum in Modern Times, such a fascinating read. It canters through nearly a century of change in art museums across the world through forty-one case studies before looking at where museums might be headed in the future. He begins with the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1939, before taking in some of the world’s biggest institutions including Tate Modern and the Saatchi Gallery in London, the Getty Center in Los Angeles, the Whitney Museum in New York, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris – as well as the Pompidou’s new Shanghai branch West Bund, which opened in 2019. It traces a radical shift from a belief that museums can and should instruct and educate, to the idea that museums should be more about contemplation, spectacle and individual experience. It’s a must read for museum-lovers, with Saumarez Smith being your clear and insightful guide on this absorbing journey. I spoke to him, to find out more.

Love museums? Then you’ll love my newsletter. I send a round up of museum news every Friday, and every two weeks a jam-packed edition of original features including interviews. Subscribe to get the next edition.

You were at the helm of three major institutions during seemingly golden years for UK museums. What was this time like?

Of course, in retrospect, the last thirty years looks like boom time! And, I think I was aware, even at the time, that I was privileged to arrive as Director of the National Portrait Gallery just after the Heritage Lottery Fund had become available, so that I was able to sit down with senior staff and talk about what we should do, with a reasonable degree of confidence that anything suggested would be possible. In fact, the Ondaatje Wing ended up being vastly more ambitious and adventurous than envisaged when we first drew up the brief, because of a sense of optimism in the period leading up to the Millennium. So, I look back on the 1990s as a period of hope and opportunity – introducing more big photographic exhibitions, broadening the remit of the collection and totally redisplaying it. Life at the National Gallery felt much tougher: never-ending important acquisitions, starting with the Madonna of the Pinks, each of which was a titanic struggle and several of which ended in ignominious failure. Maybe the government grant did go up, but only by inflation and the wage bill and costs would have increased more, so it didn’t feel like a time of plenty. Then, I moved to the Royal Academy, partly because I like big building projects and knew that the old Museum of Mankind building was the last remaining unreconstructed building in central London. What was most enjoyable at the Royal Academy was the big exhibitions: Byzantium and Bronze; Kapoor, Hockney and Kiefer. People underestimate the huge impact of the National Lottery and how it has transformed the world of culture.

Your new book details the changing nature of art museums over the past century, through individual case studies. Which do you think has had the biggest impact? And which is the most under-recognised for its impact?

I think the Centre Pompidou had a big impact, demonstrating that it was possible to do things very differently. The museum that I think has been least well recognised is the Musée d’Orsay, which I have always found impressive and interesting in the way it is laid out, but seems to have had a pretty consistently bad press, both for its architecture and in the way the collection is arranged. Maybe because it is a bit theatrical and postmodernism is so out of fashion at the moment, which means that people also under-rate the historical significance not just of the Musée d’Orsay, but Jim Stirling’s design of the Neue Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart and the Sainsbury Wing as well.

You offer particular praise for the Louvre Abu Dhabi. What makes it so impressive?

I only spent a day in Abu Dhabi and as bad luck would have it, it was a

Monday when the museum was closed. So, I spent the morning and early part

of the afternoon sitting in the sun outside it. Then, I had arranged a meeting at 4pm with Manuel Rabaté, its Director, and made a desperate plea to him to show me the collection. So, I saw it in somewhat unusual circumstances. Two things really impressed me. The first was the way the world had been subtly rebalanced to incorporate the culture and archaeology of the Middle East in a way which felt totally convincing. The second was the amazing quality of the collection, drawn not just from the Louvre, but from all the major collections in Paris. It felt like a statement of faith in the traditional idea of the museum as a representative model of the

cultures of the world.

You say that art museums are under attack? Why?

Several people have felt that the conclusion which I wrote in April 2020just after the outbreak of Coronavirus exaggerates the feeling of attack. But I do think that there are several obvious forms of current hostility towards the idea of the museum which have collided in the last year: a deep opposition to the way that Anglo-American museums are run, financed and dominated by interests of the ultra-rich; a feeling that the canon needs to be radically adjusted in order to show the work of artists whose work has traditionally been excluded; the movement behind restitution; and, lastly, Black Lives Matter. All of these in combination are creating an environment in which the museum is seen less as a democratic force for public enlightenment, and more as if it has been nothing more than a tool of Eurocentric imperialism.

The book also looks to the future - but says that “uncertainty is more absolute than at any previous time.” How worried should we be?

I ended the book on a positive note, not a negative one, because what the book demonstrates, I hope, is how resilient and adaptable the museum model has been. I hugely admired the 21st. Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, which was not an especially expensive project, but a highly inventive one and there are lots of big projects due to open in the future, including a totally reconstructed National Portrait Gallery and the V&A East. So, I don’t think we need to be so worried. As we begin to come out of COVID, there are signs of new optimism, so maybe 2020 was an apocalyptic moment which will produce a rebalancing and a reorientation of the museum project which will be healthy and not destructive.

Two of your own major projects get chapters in the book: the Ondaatje Wing at the National Portrait Gallery and the 250th anniversary revamp of the RA. What kept you awake the most while working on these projects?

I look back on the Ondaatje Wing as having been an astonishingly and, in retrospect, ridiculously straightforward project. I arrive at the NPG in January 1994. We had selected Jeremy Dixon and Edward Jones by the end of my first year. We got the majority of the funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund. My biggest anxiety was the day before it opened as to whether or not people would find their way up to the restaurant on the roof as I had insisted that the escalator should go no further than the Tudor Gallery. The revamp of the RA was much more of a headache, mainly to do with funding, but also the whole management of the project and containing its cost. However hard one tries and whatever form of contract is used, it seems to be very hard, if not impossible, to deliver a big capital project within budget. I think the Heritage Lottery Fund should do more to share knowledge and advice on best practice in project management.

The Art Museum in Modern Times discusses the recent trend for satellite museums and the franchising out of brands and collections, such as with the Louvre Lens, Guggenheim Bilbao and West Bund (a collaboration with the Centre Pompidou). Should we expect - and would it be desirable - to see the National Gallery or RA follow this route?

One of my big regrets is that the National Portrait Gallery did not open a satellite, as we planned in the late 1990s in Durham, for its enormous twentieth-century collection, which could be a rich resource for a museum of twentieth-century history. The National Gallery’s collection is not large enough to have a full satellite, but is rightly very generous with loans. At the Royal Academy, we did consider the possibility of having satellites in other parts of the world, including Singapore and Hong Kong, for travelling exhibitions. I certainly felt it could be a very good idea to send out a programme of small-scale contemporary exhibitions internationally. But the next decade is likely to be one of managing resources, not expansionism

You also say the West Bund complex in Shanghai symbolises the transformation of the art museum into something “lightweight and ephemeral.” Is this good or bad?

I admire the range of different museums on the West Bund, which are architecturally very adventurous, particularly the Long Museum, and mostly private. As I understand it, the Centre Pompidou has entered into a five-year contract for their building on the West Bund. I think the environment there is exciting, which is good. Of course, there is a risk that they are too dependent on single individuals, like Budi Tek, so may

prove to be ephemeral, which would be sad. But I have tried to describe what I see as trends in museum-building and not be too judgmental.

Should western museums be setting up new venue or outposts in China given the current claims of human rights abuses?

This is a tricky question for me to answer, given that I end the book on the West Bund and have found the opening up of museums, and indeed the engagement of the west in China more generally, as so exciting. But, of course, museums cannot, and should not, stand aside from changes in the moral and political environment.

The next major new UK museum will be V&A East in Stratford, East London. Will it be as

transformational as Tate Modern?

For me, the most interesting part of V&A East is not so much the new exhibition space, designed by O’Donnell + Tuomey, which looks to me to be aversion of a kunsthalle, but Here East [a nearby new collection and research centre, designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, which is a reinterpretation of the idea of visible storage, perhaps a version of what the V&A once was, which was acres of publicly accessible storage cabinets laid out for public and educational benefit as a kind of material culture school room. But it is hard to imagine that it will have quite the impact of Tate Modern which was such a huge public investment in, and commitment to, the culture of the modern - a revolution not just in terms of museums, but Britain’s whole attitude to contemporary art.

Which other upcoming major new global museums are you most excited about?

I’ve got a little mental checklist of projects I’m very much hoping to have a chance to see: Norman Foster’s new Museum of Antiquities in Narbonne, due to open later this year, with galleries designed by Adrien Gardère; M+ in Hong Kong also due to open later this year after over ten years planning (I went to a meeting to discuss the future of the West Kowloon Cultural District in 2008); the extension of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, designed by SANAA, due to open in 2022; Peter Zumthor’s revolutionary

design for Los Angeles County Museum due in 2023; the Museum of Narrative Art which will also open in Los Angeles in 2023; and, closer to home, of course I can’t help but be interested in the big changes to the display and layout at the National Portrait Gallery, due to re-open in 2023, and the redesign of the Sainsbury Wing due to be complete in 2024. So, there is much to look forward to.

The Art Museum in Modern Times, published by Thames & Hudson, is out in hardback now

Love museums? Then you’ll love my newsletter. I send a round up of museum news every Friday, and every two weeks a jam-packed edition of original features including interviews. Subscribe to get the next edition.